Applying Frameworks and Ethical Deliberation in Public Health

It is important to take some time to now explore some realistic ethical scenarios in public health and practice working with frameworks. Below you will find several ethical scenarios and frameworks that you can apply to these scenarios.

Activity Instructions

Applying Frameworks: Case Studies 1-4 (choose one)

After reviewing cases 1 through 4, please select one of them to work on. If you have a colleague or peer who is doing this module with you, we encourage you to work through this activity together, providing insight into different perspectives, principles and values that may surface. For whichever case you select, we invite you to use the accompanying ethical framework to help you to raise issues and deliberate about what to do. We encourage you to write down your reflections, responses, and document your engagement with the case study and your experience using the framework.

Cases 5 and 6: Reflection Questions (read both)

There are no assigned frameworks for these two cases, but rather the focus here is on key themes that arise in these two cases and answering the assigned questions.

Please feel free to share your case analyses for Case Studies 1-4 and reflections, as well as your responses to the questions for Cases 5 and 6 with the NCCHPP (ncchpp@inspq.qc.ca), as we would be very interested to hear from you and to collect course participants’ reflections. Please include the following title in the subject line of the email: “Public Health Ethics Online Module Case Studies."

Applying Frameworks: Case Studies 1-4 (choose one)

Case 1: Vaccinations

Case 1

Using the framework below to help you in your deliberation, please:

- Identify the ethical issues that arise in this case.

- Make a decision about how your health unit should respond to the member of provincial (or territorial) parliament.

- Give reasons for your decisions.

asiseeit/E+/Getty Images

Your Public Health Unit has identified that district-wide children’s vaccination rates have been declining recently, mostly due to increased opt-outs by parents.

There has been pressure from a parents’ group to shift several children’s vaccines from mandatory to optional, and to ease the opt-out requirements as well. This group has become more vocal recently, and they have the attention of local and provincial politicians.

Your member of provincial parliament is on a steering committee considering provincial regulations around school-age vaccination requirements. They want your advice on whether to continue with existing regulations. You have also been asked to explain how the status quo can be defended: why should certain vaccinations be mandatory, contra the freedom of parents to choose for their children?

How do you respond to your member of provincial parliament? Use the following framework to raise the ethical issues at play in this scenario and come up with a strategic response. (NCCHPP, 2018)

The adapted 2-page summaries of frameworks and links to the originals are here:

Repertoire - Ethics Frameworks for Public Health![]()

Note: direct links to the frameworks and to the adapted summaries may be found below, in the reference material for each framework that is to be applied to each of the four cases.

Framework: Schröder-Bäck et al. (2014).

Teaching seven principles for public health ethics: Towards a curriculum for a short course on ethics in public health programmes![]() .

.

Schröder-Bäck, P., Duncan, P., Sherlaw, W., Brall, C., & Czabanowska, K. (2014). BMC Medical Ethics 2014, 15(73).

Our Adapted Summary of a Public Health Ethics Framework![]() .

.

Framework goal:

The authors set out to produce a short, case-based teaching course in ethics for students in public health because in their view, practitioners must often face “difficult situations in which they have to make decisions with explicitly moral dimensions and yet they receive little training in the area of ethics” (2014, p. 9). The course outline is readily amenable to adaptation and use as an ethics framework.

Framework structure:

The first part of this summary outlines seven ethical principles. From the outset, each is to be considered as equal in importance to the others. The second part presents a series of steps for ethical reasoning and decision making.

-

Seven principles

- Non-maleficence

Will the proposed intervention harm anyone? - Beneficence

Will the intervention benefit every involved/affected individual? - Health Maximization

Is the intervention effective and evidence-based? Does it improve the health of the population? - Efficiency

Is the intervention cost-effective? Would the resources be better directed to another option? - Respect For Autonomy

Does the intervention involve coercion? Is it paternalistic? Does it promote autonomy? Are personal data/privacy handled appropriately? - Justice

Does the intervention involve or provoke any stigmatization, discrimination or exclusion? Will it reduce or increase social and health inequalities (inequities)? Will vulnerable sub-populations be considered and supported? Will it enhance or corrode social cohesion and solidarity? - Proportionality

Among the possible alternatives, does the intervention impose the least burdens upon people? Are its burdens in proportion with its hoped-for outcomes?

- Non-maleficence

-

Steps of applied ethical reasoning

- Identify the issue in your own words: What is the underlying moral conflict?

- Identify the issue in ethical words: Which principles apply here? How do we interpret them in this case? Which ones are in conflict with others?

- Do we have all the information we need? What do we need to learn more about?

- What alternatives are there? Are they feasible? Do they reduce moral issues or tensions?

- Further interpretation of principles: With more information, does your interpretation change?

- Weighing: Are all conflicting principles still of equal value? Does your interpretation push one or more into priority?

- What do we conclude? What is our solution to the problem?

- Integrity: Does the solution seem appropriate and acceptable? If it were to be implemented, could we live with it?

- Act and try to convince others based on your ethical reasoning and judgment.

Case 2: Healthy Food Program

Case 2

Using the framework below to help you in your deliberation, please:

- Identify the ethical issues that arise in this case.

- Make a decision about whether your health unit should

- Approve this project

- Approve a modified version of the project

- Reject this project / propose an alternative.

- Give reasons for your decisions.

fcafotodigital/E+/Getty Images

A recent news report has identified several areas in your city’s core neighbourhoods as food deserts. Food deserts are said to exist in low-income areas where residents do not have access (within 1 km) to a supermarket or a full‐service grocery store (min. 10 000 square feet). They are often indicative of a host of interrelated economic, social and health inequalities in the lives of local residents.

Your health unit has been asked to provide a letter of support for the city’s 'Healthy Food for All' program, and later to provide in-kind support from health unit staff (.25-.5 FTE).

One of the program’s key elements is an incentive for any supermarket or full-service grocery store that opens in an identified food desert in the next 3 years. These new stores would benefit from a 5‐year tax rebate, co‐financed by the city and the province.

How do you respond?

(NCCHPP, 2016)

Framework: ten Have et al. (2012).

An ethical framework for the prevention of overweight and obesity: A tool for thinking through a programme's ethical aspects![]() .

.

ten Have, M., van der Heide, A., Mackenbach, J., & de Beaufort, I. D. (2012). European Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 299-305.

Framework goal:

for making transparent what the potentially ethically problematic aspects of a programme are and for evaluating to what extent a programme to prevent overweight or obesity is acceptable from an ethical point of view

Framework structure:

- 1st part: 8 questions to inform the deliberation.

- 2nd part: 8 steps for doing the deliberation.

1st part

How does the program affect:

- Physical health?

- Psychosocial well-being?

- Equality?

- Informed choice?

- Social and cultural values?

- Privacy?

- Attribution of responsibilities?

- Liberty?

2nd part

- Describe the program's main ethical weaknesses.

- Describe its main ethical strengths.

- Discuss whether it is possible to adjust the program in order to maximize its weaknesses.

- Discuss whether the program is likely to be effective in preventing overweight and obesity.

- Discuss whether the program's strengths outweigh its weaknesses.

- Discuss whether there is an alternative program with fewer ethical weaknesses.

- Discuss whether sound justification can be provided for the remaining weaknessess.

- Define whether and under what conditions the program is acceptable from an ethical point of view.

Case 3: Healthy Babies Healthy Children

Case 3

Using the framework below to help you in your deliberation, please:

- Identify the ethical issues that arise in this case (please note that issues appear at several levels here, interpersonal, institutional, and policy levels).

- Make a decision about what you should do, what your employer should do, and what policy implications should be addressed.

- Give reasons for your decisions.

You are a public health professional, a Healthy Moms and Healthy Kids program home visitor. Today you met with Cindy and her 6-month old baby. Cindy lives in a city high-rise. During the visit, she said that she is going to be evicted from her apartment for smoking pot there. The building (and several others owned by the same company) has been designated a tobacco and cannabis-free building since 2016 when all tenants were required to sign new leases. Cindy says she signed it but had no choice. She says she only smokes a bit to calm her nerves and that there is nowhere she is allowed to smoke cannabis or even tobacco any more. Pot’s legal now and as far as I know it’s only rich people who can get high in their own houses without consequences, she says. She shows the landlord’s letter stating that this third offense means eviction.

You are worried about Cindy’s well-being as well as that of her baby. She is living on a very low income and has nowhere else to go. She is a single mom with few social connections. She previously had a part-time job with a cleaning company but had to quit during her pregnancy. She has no access to a daycare and can only occasionally leave her child with a neighbour. You are also concerned about the effects of secondhand smoke on her child. Your focus with Cindy has been on managing stress, healthy eating and taking care of her baby.

As a community health nurse, you are aware that Cindy is not alone in this kind of situation, but you feel powerless to change policies, much less keep up with the demands of your caseload. You did not think that cannabis use was the most pressing of Cindy’s problems, but now she might lose her home. What should you do?

(NCCHPP, 2018, unpublished)

Framework: Kass, N. E. (2001).

An ethics framework for public health![]() .

.

Kass, N. E. (2001). American Journal of Public Health, 91(11), 1776–1782.

Framework goal:

to help public health professionals consider the ethics implications of proposed interventions, policy proposals, research initiatives, and programs

Note on this case: this involves at least two policies/interventions/programs, the home visiting program and the multi-unit residential policies on cannabis use which are consistent with provincial legislation. This case also has a strong focus on the micro-level concern relating to the well-being of C., her baby, and the home visitor. As you proceed through the questions proposed by Kass, please adapt as you see fit.

Framework structure:

6 questions

- What are the public health goals of the proposed program?

The ultimate health goals - How effective is the program in achieving its stated goals?

The ’greater the burdens placed by a program’ (liberty, costs, etc.) the stronger the evidence should be. - What are the known or potential burdens of the program?

What are the risks to: Privacy and confidentiality? Liberty and self determination? Justice? Individuals’ health? - Can burdens be minimized? Are there alternative approaches?

“[W]e are required, ethically, to choose the approach that poses fewer risks to other moral claims, such as liberty, privacy, opportunity, and justice, assuming benefits are not significantly reduced” (p. 1780). - Is the program implemented fairly?

Is there a fair distribution of benefits and burdens? Will the program increase or decrease inequalities? Is there a risk of stigmatizing certain groups? - How can the benefits and burdens of a program be fairly balanced?

“[T]he greater the burden imposed by a program, the greater must be expected public health benefit”. The more that “burdens are imposed on one group to protect the health of another...the greater must be the expected benefit” Balancing these calls for a democratic, equitable process.

Case 4: Heat Wave Response

Case 4

Using the framework below to help you in your deliberation, please:

- Identify the ethical issues that arise in this case.

- Make a decision about whether your health unit should

- Approve this project (i.e., moving at-risk individuals to cooling centres in other neighbourhoods).

- Approve a modified version of the project

- Reject this project / propose an alternative.

- Give reasons for your decisions.

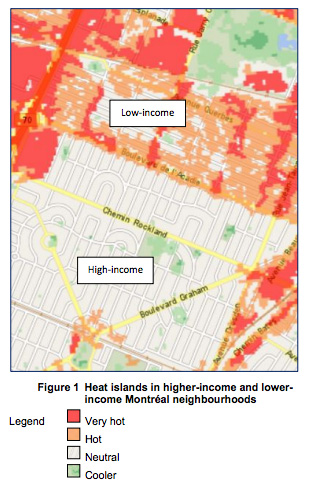

Your health unit has been asked to review the municipality’s Heat Alert and Response Plan.

One of the plan’s key elements is the provision of neighbourhood cooling centres during heat waves. However, some neighbourhoods, particularly low-income areas where the need is greatest, are thought to lack suitable facilities for cooling centres.

One option is to bus at-risk individuals to air conditioned shopping malls, community centres, sports facilities, etc. in other neighbourhoods. (NCCHPP, 2015)

Source: http://geoegl.msp.gouv.qc.ca/gouvouvert/?id=temperature. This open data is used under the open data use licence of the governmental administration available at this web address: www.données.gouv.qc.ca. The granting of this licence does not imply endorsement by the governmental administration of the use which is made of that data [Translation]. Licence: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/infra-geoouverte/igo/master/LICENSE_ENGLISH.txt

Some additional considerations about heat wave relief:

- Cool environments work (NCCEH, 2008; O’Neill et al., 2009) … but it is not a case of “if you build it, they will come”.

- The most vulnerable tend to not want to leave their neighbourhoods (Merkes, 2014).

- Many do not identify themselves as at risk (Merkes, 2014).

- People with mental illness are particularly at risk (Price, Perron, & King, 2013).

Framework: Marckmann et al. (2015).

Marckmann, G., Schmidt, H., Sofaer, N., & Strech, D. (2015). Putting public health ethics into practice: a systematic framework![]() . Frontiers in public health, 3(23), 1-8.

. Frontiers in public health, 3(23), 1-8.

Our adapted summary is available at: Adapted Summary of a Public Health Ethics Framework.

Framework goal:

[To] guide professionals in planning, conducting, and evaluating PH interventions [in a way that] explicitly ties together ethical analysis and empirical evidence, thus striving for evidence-based PHE

Framework structure:

First part – Respond to the following questions, in order.

- What are the expected benefits of the intervention for the target population?

(List the potential beneficial effects. Time permitting, consider their magnitude, likelihood, relevance and whether alternatives will have greater or lesser benefits.) - What are the potential burdens and harms of the intervention?

(List the potential negative effects. Time permitting, consider their severity, likelihood, relevance and whether alternatives will have greater or lesser harms.) - How does the intervention affect the autonomy of the individuals in the target population?

(Consider: Health-related empowerment? Autonomous choice? Privacy and confidentiality?) - Impact on equity: how are benefits and burdens distributed?

(Consider: Access for all? Impact on health disparities? Compensation for any harms done?) - Expected efficiency: is it cost-effective?

Second part – Discuss and respond to the following questions:

- Can you identify some tensions between the 5 criteria (benefits, harms, autonomy, equity and efficiency) highlighted in the previous questions?

- For each tension, which criterion should prevail? Why?

- Is there a way to make the program more acceptable?

- Is there an ethically less challenging program or intervention that can achieve the same goal?

Cases 5 and 6: Structural violence and the limitations of frameworks

Reflection Questions: Case Studies 5 and 6 (read both)

There is no assigned framework for these case studies. Your task here is to reflect on the listed themes as you address the following questions:

- advocacy;

- global health;

- inequities and social justice;

- racism, and structural violence.

Please take a few minutes to reflect and to make notes before you respond.

- What are the boundaries of a Canadian public health practitioner’s responsibilities? Do those responsibilities extend to Wanda? To Acéphie?

- Clearly, public health alone cannot change the factors that produce the suffering faced by Acéphie and by Wanda. In order to make a difference, what other sectors would public health have to work with?

- What concrete actions might help?

The following stories, and the kinds of reflection that they engender, are essential to public health ethics.

These cases highlight macro-level issues, namely the political economy. These stories call on us to consider power dynamics in society and the influences that shape the economic, social and environmental policies that produce suffering for individuals. In Canada, many practitioners meet individuals suffering from structural violence (the non-arbitrary assignment of higher risk upon some people and not others is a result of macro-level forces… policies, yes, and the structures of power that shape them).

Read

Acéphie’s story

in Paul Farmer’s On Suffering and Structural Violence: A View from Below![]()

Wanda’s Story

in Caroline L. Tait’s Resituating the Ethical Gaze: Government Morality and the Local Worlds of Impoverished Indigenous Women![]()

There are a few points to make about these two stories and what they might say for public health ethics:

- These are public health issues.

- There is no algorithm, no easy solution.

- Social justice to address structural violence is both a local public health issue and a global public health issue.

- Moral distress can arise from feeling as though one cannot really do what is needed to help. (How can a practitioner working within the system help Acéphie? Wanda?)

For a concrete example of structural violence related to Wanda’s story, Tait mentions policies that permit multiple foster-care placements and the compelling evidence “documenting the elevated health and social risks caused to the child by this practice” (Tait, 2013, p. 4). And practitioners are expected to help, to make a difference.

Susan Sherwin notes that “bioethicists generally have ignored the collective impact of the large moral problems facing us in favor of attending to more modest, familiar ones with a well-defined scope” (Sherwin, 2008, p. 8.) and she calls for a broader scope and ambition for a public ethics to begin to take on collective problems at the individual and the macro levels simultaneously. One might argue that there has been movement in public health ethics in the past decade, but there is much more to be done.

The concerns of public health involve these stories and their implications cannot all be easily taken in and understood, much less resolved. The stories ought to help us to remain humble in our work and to realize that we cannot resolve things with an ethics framework and an hour or two of deliberation. Sherwin’s work is very helpful in drawing our focus to the most important questions and in not being seduced by what might appear to be easy-to-resolve and therefore desirable problems/ solutions/ approaches.

Readings

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). (2015).![]() Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

Farmer, Paul. (2005). Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Whither Bioethics Now? The Promise of Relational Theory![]()

Sherwin, S. & Stockdale, K. (2017). International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 19(1), 7-29.

Collections of case studies

University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. (2013). Population and Public Health Ethics: Cases from Research, Policy, and Practice![]() . Toronto: Joint Centre for Bioethics.

. Toronto: Joint Centre for Bioethics.

Barrett, D.H., Ortmann, L.H., Dawson, A., Saenz, C., Reis, A., Bolan, G. (Eds.). (2016). Public Health Ethics: Cases Spanning the Globe![]() . New York: Springer. Open access as eBook.

. New York: Springer. Open access as eBook.

Coughlin, S. S. (2009). Case Studies in Public Health Ethics, 2nd Edition. Washington: American Public Health Association.

Nova Scotia Health Ethics Network (NSHEN). (2018). Ethics Case Database![]() .

.

Websites of Interest

University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics![]()

Nova Scotia Health Ethics Network![]()

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Public Health Ethics Page![]()

Public Health Ontario. Ethics![]()

British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC). BCCDC ethics - Case studies using a framework (recorded presentation)![]()

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Public health ethics![]()